Not as smooth as silk

DR KATYA MUSCAT, DR DONIA GAMOUDI, DR AARON SCHEMBRI, DR VALESKA PADOVES

ABSTRACT

Genital ulceration is a common presentation to general practitioners, dermatologists, gynaecologists and genitourinary physicians alike. Differential diagnosis is broad and includes sexually transmitted infections (STIs) and other non-infectious conditions such as malignancies, skin diseases and drug allergies.

This case report describes a case of genital herpes virus infection triggering Behçet’s disease (BD). As current treatment options for BD remain limited and often unsatisfactory, more research into the pathogenesis will hopefully lead to the development of successful therapeutic strategies in the near future.

Keywords: FGM, genital, HSV, ulcer, Behçet’s

CASE REPORT

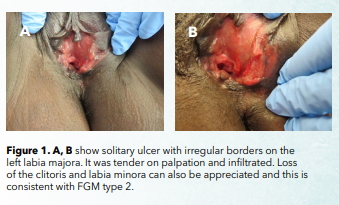

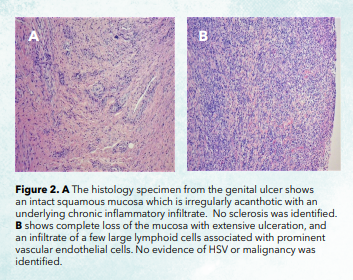

A 37-year-old Ethiopian refugee, married to a conational and mother of two children, was referred to the Genito-urinary clinic (GUC) in view of a 5-year history of painful intermittent oral and genital ulceration. The rest of her medical and sexual history was unremarkable. She had tested negative for blood[1]borne viruses (HIV, Hepatitis B and C) and syphilis before referral. Examination revealed multiple oral ulcers and a solitary, tender, infiltrated ulcer with irregular borders on the left labia majora and loss of the clitoris and labia minora, the latter consistent with female genital mutilation (FGM) type 2. Skin scarring was also present (Figure 1). A polymerase chain reaction (PCR) swab from the genital ulcer was requested for herpes simplex virus (HSV) and Treponema pallidum, resulting in the detection of HSV-1. A swab taken from the oral ulcer was negative for HSV. A course of aciclovir 400mg three times a day for 7 days was initiated but no improvement was seen at follow-up. Haematological and biochemical blood investigations were normal except for slightly raised inflammatory markers. HLA-B*51 was negative. A biopsy from the edge of the genital ulcer was performed and histopathological features are described in Figure 2A and B, which excluded HSV [HSV was however detected in the PCR, discussed earlier]. No signs of uveitis or hypopyon were detected on slit lamp examination. This was done to investigate Behcet’s disease. The patient was started on a course of prednisolone 40mg daily which was then tailed down gradually over 8 weeks. At follow-up, the oral and genital ulcers had resolved. On cessation of the steroids, the patient experienced a recurrence of oral and genital ulceration and once again HSV-1 was detected from the genital lesion.

The diagnosis of Behçet’s disease (BD) was formulated on clinical criteria, response to immunosuppressive treatment and exclusion of other conditions. The trigger factor in this case was thought to be HSV-1. The patient was started on prednisolone, and colchicine 0.5mg twice a day thereafter as a steroid-sparing agent. One year later, the patient remains well and free from symptoms.

DISCUSSION

BD, also known as ‘Silk Road disease’ as this condition is considered more prevalent in the areas surrounding the old silk trading routes in the Middle East and Central Asia, is a rare immune-mediated systemic vasculitis.1 Whereas epidemiological studies have been carried out in Asia and Europe, data from African regions are scanty and only few cases have been reported in the literature.2 The disease’s aetiology is unknown but the most widely held hypothesis is that of a profound inflammatory response triggered by an infectious agent in a genetically susceptible host.3 HSV, hepatitis, mycobacteria and Helicobacter pylori have all been implicated.4 The genetic susceptibility has been linked to HLA-B*51. However, expression of this antigen is neither sensitive nor specific as a diagnostic test.5

Although BD is relatively a new disease (described in 1937), it has already 16 sets of classification criteria.6 Recurrent oral and genital ulcerations are highly discriminatory diagnostic criteria. Morphologically, genital ulcers are deeper, larger and can take longer to heal. Genital scarring is usually a strong evidence of the presence of BD. Reactivation of HSV infection could have triggered BD,4 but unlikely to be the sole agent responsible for the ulceration. The lack of response to antiviral treatment with nucleoside analogues is uncommon in immunocompetent hosts with antiviral resistance reported as low as 0.3%.7 The diagnosis of HSV-induced necrotising granuloma was also considered. In the literature, there are several reports of granulomatous reactions at sites of previous varicella zoster virus infection,8 but only 2 case reports of HSV-induced granuloma.9 However, the absence of a granulomatous infiltrate on histology excluded this diagnosis as well as malignancy.

The scarring which persisted after the vulval biopsy and after healing of the genital ulceration, led to a lot of anxiety and psychological distress. Our patient was therefore referred to the plastic surgical team for consideration of surgery. FGM is recognized in international law as a human rights violation, but it remains deeply entrenched in the cultures in which it is practised.10 In some African countries, FGM is performed for cosmetic reasons and regarded as a procedure that improves women’s desirability.

To conclude, diagnosing BD in non-endemic regions is often delayed and has to be decided on clinical grounds, with due diligence in excluding other conditions. Although BD’s prognosis is good, flare ups can have a negative impact on the psychosexual health and wellbeing of the affected person. In migrants, cultural aspects must also be considered and a more comprehensive approach to diagnosis and treatment adopted.

REFERENCES

- Akdeniz N, Elmas ÖF, Karadağ AS. Behçet syndrome: A great imitator. Clin Dermatol. 2019; 37:227-239.

- Ndiaye M, Sadikh Sow A, Valiollah A et al. Behçet’s disease in black skin. A retrospective study of 50 cases in Dakar. J Dermatol Case Rep. 2015; 31(9):98–102.

- Seyahi E. Phenotypes in Behçet’s syndrome. Intern Emerg Med. 2019; 14:677-689.

- Do Young Kim, Suhyun C, Min Ju Choi et al. Immunopathogenic role of Herpes simplex virus in Behçet’s disease. Genet Res Int. 2013; 2013:638273.

- Graham R. Wallace. HLA-B*51 the primary risk in Behçet’s disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014; 111:8706–8707.

- Davatchi F. Diagnosis/Classification Criteria for Behcet’s Disease. Patholog Res Int. 2012; 2012:607921.

- Bacon TH, Levin MJ, Leary JL et al. Herpes simplex virus resistance to aciclovir and penciclovir after 2 decades of antiviral therapy. Clin Microbiol Rev 2003; 16:114–128.

- Natalie A Wright, Carlos A Torres-Cabala, Jonathan L Curry et al. Post-varicella-zoster virus granulomatous dermatitis: A report of 2 cases. Cutis 2014 Jan; 93(1):50-4. Differential Diagnosis and Management of Behçet Syndrome. Nat Rev Rheumatol 2013; 9:79-89.

- M. Sivendran, E.Hossler, T.Ferringer. Herpes simplex virus-induced necrotising granuloma formation. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology 2014; 70:112-113.

- WHO. Female Genital Mutilation. Published in February 2020. Available at https://www.who.int/en/news-room/fact-sheets/ detail/female-genital-mutilation