From Dada to Surrealism beyond borders

by Prof. Francesco Carelli

The word ‘surrealism’ was first coined in March 1917 by Guillaume Apollinaire. He wrote in a letter to Paul Dermée: “All things considered, I think in fact it is better to adopt surrealism than supernaturalism, which I first used”

Apollinaire used the term in his program notes for Sergei Diaghilev‘s Ballets Russes, Parade, which premiered 18 May 1917. Parade had a one-act scenario by Jean Cocteau and was performed with music by Erik Satie. Cocteau described the ballet as “realistic”. Apollinaire went further, describing Parade as “surrealistic”.

This new alliance—I say new, because until now scenery and costumes were linked only by factitious bonds—has given rise, in Parade, to a kind of surrealism, which I consider to be the point of departure for a whole series of manifestations of the New Spirit that is making itself felt today and that will certainly appeal to our best minds. We may expect it to bring about profound changes in our arts and manners through universal joyfulness, for it is only natural, after all, that they keep pace with scientific and industrial progress. (Apollinaire, 1917)

The term was taken up again by Apollinaire, both as subtitle and in the preface to his play Les Mamelles de Tirésias: Drame surréaliste, which was written in 1903 and first performed in 1917.

World War I scattered the writers and artists who had been based in Paris, and in the interim many became involved with Dada, believing that excessive rational thought and bourgeois values had brought the conflict of the war upon the world. The Dadaists protested with anti-art gatherings, performances, writings and art works. After the war, when they returned to Paris, the Dada activities continued.

During the war, André Breton, who had trained in medicine and psychiatry, served in a neurological hospital where he used Sigmund Freud‘s psychoanalytic methods with soldiers suffering from shell-shock. Meeting the young writer Jacques Vaché, Breton felt that Vaché was the spiritual son of writer and pataphysics founder Alfred Jarry. He admired the young writer’s anti-social attitude and disdain for established artistic tradition. Later Breton wrote, “In literature, I was successively taken with Rimbaud, with Jarry, with Apollinaire, with Nouveau, with Lautréamont, but it is Jacques Vaché to whom I owe the most.”

Back in Paris, Breton joined in Dada activities and started the literary journal Littérature along with Louis Aragon and Philippe Soupault. They began experimenting with automatic writing—spontaneously writing without censoring their thoughts—and published the writings, as well as accounts of dreams, in the magazine. Breton and Soupault continued writing evolving their techniques of automatism and published The Magnetic Fields (1920).

By October 1924 two rival Surrealist groups had formed to publish a Surrealist Manifesto. Each claimed to be successors of a revolution launched by Appolinaire. One group, led by Yvan Goll consisted of Pierre Albert-Birot, Paul Dermée, Céline Arnauld, Francis Picabia, Tristan Tzara, Giuseppe Ungaretti, Pierre Reverdy, Marcel Arland, Joseph Delteil, Jean Painlevé and Robert Delaunay, among others. The group led by André Breton claimed that automatism was a better tactic for societal change than those of Dada.

As they developed their philosophy, they believed that Surrealism would advocate the idea that ordinary and depictive expressions are vital and important, but that the sense of their arrangement must be open to the full range of imagination according to the Hegelian Dialectic.

Freud’s work with free association, dream analysis, and the unconscious was of utmost importance to the Surrealists in developing methods to liberate imagination. They embraced idiosyncrasy, while rejecting the idea of an underlying madness. As Dalí later proclaimed, “There is only one difference between a madman and me. I am not mad.”

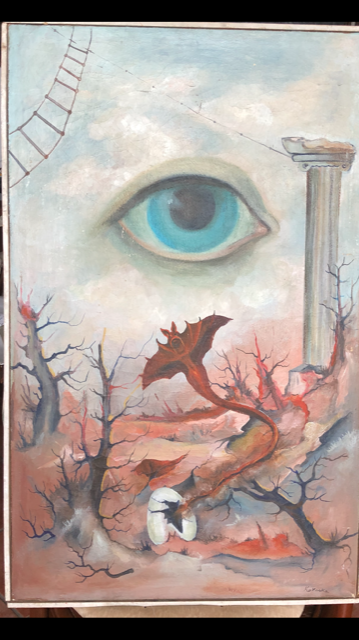

Beside the use of dream analysis, they emphasized that “one could combine inside the same frame, elements not normally found together to produce illogical and startling effects.” Breton included the idea of the startling juxtapositions in his 1924 manifesto, taking it in turn from a 1918 essay by poet Pierre Reverdy, which said: “a juxtaposition of two more or less distant realities. The more the relationship between the two juxtaposed realities is distant and true, the stronger the image will be−the greater its emotional power and poetic reality.”

The group aimed to revolutionize human experience, in its personal, cultural, social, and political aspects. They wanted to free people from false rationality, and restrictive customs and structures. Breton proclaimed that the true aim of Surrealism was “long live the social revolution, and it alone!” To this goal, at various times Surrealists aligned with communism and anarchism.

In 1924 two Surrealist factions declared their philosophy in two separate Surrealist Manifestos. That same year the Bureau of Surrealist Research was established, and began publishing the journal La Révolution surréaliste. .

Goll and Breton clashed openly, at one point literally fighting, at the Comédie des Champs-Élysées, over the rights to the term Surrealism. In the end, Breton won the battle through tactical and numerical superiority. Though the quarrel over the anteriority of Surrealism concluded with the victory of Breton, the history of surrealism from that moment would remain marked by fractures, resignations, and resounding excommunications, with each surrealist having their own view of the issue and goals, and accepting more or less the definitions laid out by André Breton.

Breton’s 1924 Surrealist Manifesto defines the purposes of Surrealism. He included citations of the influences on Surrealism, examples of Surrealist works, and discussion of Surrealist automatism. He provided the following definitions:

Dictionary: Surrealism, n. Pure psychic automatism, by which one proposes to express, either verbally, in writing, or by any other manner, the real functioning of thought. Dictation of thought in the absence of all control exercised by reason, outside of all aesthetic and moral preoccupation.

The movement in the mid-1920s was characterized by meetings in cafes where the Surrealists played collaborative drawing games, discussed the theories of Surrealism, and developed a variety of techniques such as automatic drawing. Breton initially doubted that visual arts could even be useful in the Surrealist movement since they appeared to be less malleable and open to chance and automatism. This caution was overcome by the discovery of such techniques as frottage, grattage and decalcomania.

Soon more visual artists became involved, including Giorgio de Chirico, Max Ernst, Joan Miró, Francis Picabia, Yves Tanguy, Salvador Dalí, Luis Buñuel, Alberto Giacometti, Valentine Hugo, Méret Oppenheim, Toyen, Kansuke Yamamoto. Though Breton admired Pablo Picasso and Marcel Duchamp and courted them to join the movement, they remained peripheral. More writers also joined, including former Dadaist Tristan Tzara, René Char, and Georges Sadoul.

In 1925 an autonomous Surrealist group formed in Brussels. The group included the musician, poet, and artist E. L. T. Mesens, painter and writer René Magritte, Paul Nougé, Marcel Lecomte, and André Souris. In 1927 they were joined by the writer Louis Scutenaire. They corresponded regularly with the Paris group, and in 1927 both Goemans and Magritte moved to Paris and frequented Breton’s circle. The artists, with their roots in Dada and Cubism, the abstraction of Wassily Kandinsky, Expressionism, and Post-Impressionism, also reached to older “bloodlines” or proto-surrealists such as Hieronymus Bosch, and the so-called primitive and naive arts.

André Masson‘s automatic drawings of 1923 are often used as the point of the acceptance of visual arts and the break from Dada, since they reflect the influence of the idea of the unconscious mind. Another example is Giacometti’s 1925 Torso, which marked his movement to simplified forms and inspiration from preclassical sculpture.

However, a striking example of the line used to divide Dada and Surrealism among art experts is the pairing of 1925’s Little Machine Constructed by Minimax Dadamax in Person (Von minimax dadamax selbst konstruiertes maschinchen) with The Kiss (Le Baiser) from 1927 by Max Ernst. The first is generally held to have a distance, and erotic subtext, whereas the second presents an erotic act openly. In the second the influence of Miró and the drawing style of Picasso is visible with the use of fluid curving and intersecting lines and colour, whereas the first takes a directness that would later be influential in movements such as Pop art.

Photo: surrealistic oil on canvas