Bruno Munari – A Multifaceted creative mind, A method for children

By Francesco Carelli Professor Family Medicine, Milan and Rome

Munari’s aesthetic develop from his initial Futurist phase (around 1927) to the post-war period (up to 1950) when, as one of the founders of the Movimento Arte Concreta, beccame a point of reference for a new generation of Italian artists. His pioneering work exerted an influence that stretched far beyond the borders of his native country; he was one of the most complex, creative and multi-faceted figures of Italian 20th century art.

Bruno Munari was born in Milan in 1907, and lived and worked there until 1998, the year of his death. He began his career within the Futurist movement and was considered by F. T. Marinetti to be one of its most promising young exponents. From the very beginning, he was concerned with exploring the possibility of representing painting spatially through a continuous flow of forms rendered mutable through the incorporation of a temporal dimension, in accordance with the theories of Giacomo Balla and Fortunato Depero in their 1915 Manifesto ‘Futurist Reconstruction of the Universe’.

Munari described the roots of his work as his ‘Futurist past’, and the movement’s ambitious scope certainly informed his kaleidoscopic career, leading him to work across a range of media and disciplines from painting to photomontage, sculpture, graphics, film and art theory. Indeed, his influences were extremely varied, also reflecting the aesthetics and sensibilities of movements such as Constructivism, Dada, and Surrealism.

In 1930, he began designing his Useless Machines – the first ‘mobiles’ in the history of Italian art – the aim of which was to liberate abstract painting from its static nature by employing the principle of causality introduced by the use of air as a force of movement for the suspended parts. The paradoxical name was intended to be a reflection on the usefulness of the useless (art) and the uselessness of the useful (machines), creating a distinction between his personal aesthetic and that of ‘orthodox’ Futurism, with its fascination with roaring machinery and its uncritical attitude towards progress.

In Paris in 1946, he created his first spatial environment entitled Concave-convex, based once again around a hanging object made of metallic mesh carefully moulded in such a way as to recall certain forms studied in topology, such as the Möbius strip. This was installed in semi-darkness and illuminated by spotlights thereby generating shadows and reflections, many of which recall the moiré patterns of certain kinetic paintings of the 1960s. Along with the spatial environments of Lucio Fontana, the Concave-convex represents one of the first installations in the history of modern European art.

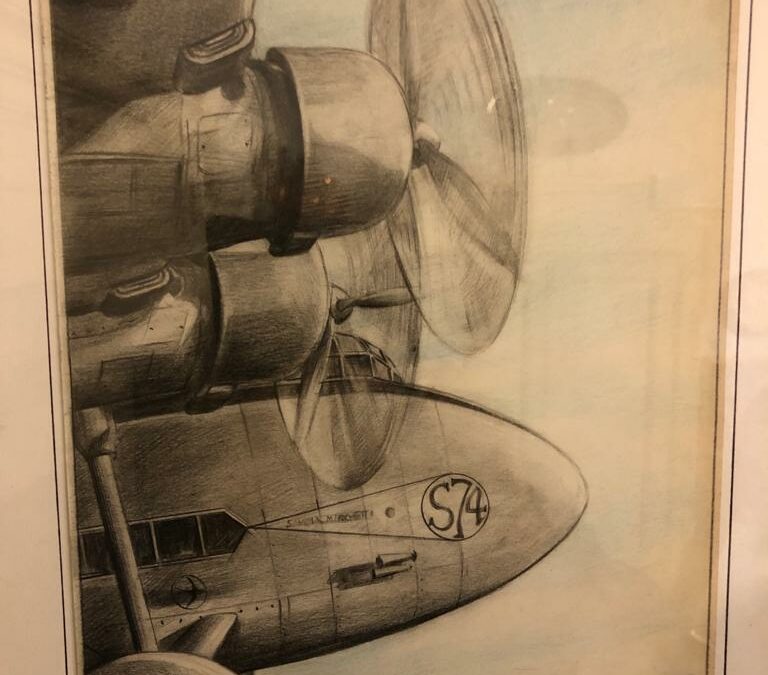

During the 1920s and ‘30s Munari acted as a consultant or art director for such important magazines as L’Ala d’Italia, La rivista illustrata del Popolo d’Italia, Natura, La lettura, L’almanacco letterario Bompiani, Tempo and Domus, and for the publicity projects of companies such as Campari, Snia Viscosa, Pirelli, Olivetti and Agip.

Towards the end of the 1940s, together with Atanasio Soldati, Gianni Monnet, Gillo Dorfles, Galliano Mazzon and others, Munari founded the M.A.C. (Movimento Arte Concreta or Concrete Art Movement) in Milan. This movement acted as a catalyst for Italian abstraction, giving rise to a ‘synthesis of arts’ capable of complementing traditional painting with new tools of communication and able to demonstrate the possibility of a convergence between art and technology, creativity and functionality, in an industrial context.

During the 1950s, he created the series of Negative-positives, abstract compositions in which the classic dualism between the figure and the background vanishes due to a visual perception made unstable by the lack of an edge or boundaries within the composition. In 1950, he continued to explore the notion of painting with light, arriving at the process of dematerialising art through the use of projection slides in works known as Direct Projections. The artist created compositions with cheap materials or debris such as coloured and transparent plastic, organic elements and cotton threads, which were sandwiched between two glass surfaces. The compositions thus created were projected not only indoors but also outdoors, on the façades of buildings, giving them a feeling of monumentality.

In 1951, he created the series of Arrhythmic Machines, the irregular movements of which were generated through the use of springs. In 1953, he discovered, for the first time in history, how to break the light spectrum through a Polaroid lens in a continuum given by the rotating movement of a polarising filter applied to a slide projector. The Polaroid Projects were born as logical continuations of, and theoretical complements to, the research that led to the creation of his Direct Projections.

Munari’ last years of life were dedicated to study plurisensorial experience in children, when they are in Zen area, when they meet reality by playing. All sensorial receptors are open to get data: to see, to touch, to taste, to perceive warmness, coldness, weight, lightness, smooth and hard, rough and flat, forms, distances, light , sound and silence, all is now, all can be learned and play facilitates memory. After that, we become to be adult, we enter in ” the society ” , one by one all sensorial receptors are closing. We learn near nothing more, we use only sense and word and we ask to ourselves: how much cost ? what is this for ? how much can I get form this ? and in his books for children he indicates a pedagogic method now continued in schools by his son , through a Foundation.