Malevich, hero with mannequins

by Prof. Francesco Carelli – University of Milan, Rome

Kazimir Malevich (1878-1935) was a radical, mysterious and hugely influential figure in modern art. He lived and worked through one of the most turbulent periods in twentieth century history.

His early experiments as a painter led him towards the cataclysmic invention of Suprematism, a bold visual language of abstract geometric shapes and stark colours, epitomised by the Black Square. A definitively radical gesture, it was revealed to the world after months of secrecy and was hidden again ( because of Soviet Regime ) for almost half a century after its creator’s death. It sits on a par with Duchamp’s ‘readymade’ as a game-changing moment in twentieth century art and continues to inspire and confound viewers to this.

Death of an Hero

Malevich, in his struggle with the banal daily existence, was under constant criticism from opponents in both the artistic community and the Soviet regime. He met with open reprisals following his return from his sole foreign trip to Poland and Germany in 1927. These included unfair and thoughtless administrative decisions as well as actions by the security services, undertaken until the last days of his life. And after his death too, in the form of a ban on the public presentation of his works in the Soviet Union.

Even his very name was banned, some were aware of the persecuted artist’s greatness and tried to protect him soughting out ways to circumvent regulations in the name of higher values. Still, they were obliged to follow orders from ‘above’ (meaning the KGB).

From the very birth of Bolshevik Russia – there was a more or less brutal smear campaign against the artist. Open and covert, via the press and artistic organisations subordinated to the party’s directives. Several arrests, first time in Vitebsk ( he was saved then by a letter from Lunacharsky they found on him ). Suspicions of involvement in subversive, anti-state activities (imagine UNOVIS he directed in Vitebsk, was one of the most revolutionary artistic experience for new and free visions ). Oppressive, humiliating censorship from the local authorities (1919-1921) drove to the beginnings of starvation-induced tuberculosis.

Being under constant surveillance from secret agents or planted provocateurs ( a mixture of truth and fabrication ) he was in poverty with sporadic purchases of his works by museums or collectors, touching concern for his family, mother, wife, daughter, in trouble to secure a bread ration for them.

His wife Zofia felt ill with tuberculosis, lacking of money for medications. During his experiments and his teaching ( Artistic Culture Institute, INChUK ), he was harassed by constant inspections with the real threat of the unique institution’s liquidation. A smear campaign in the press was the prelude to a larger offensive from the conservative circles. He planned for staging an exhibition abroad presenting his oeuvre and research method. There was only a first and only trip to Warsaw ( days of enthusiastic welcome ) and Berlin ( he met the Bahaus’s founders ! opening the next steps for new development in art in Western Europe ) , under close KGB surveillance with sudden orders to return immediately ( it is known today by whom issued, reasons remain a mystery… or clear ). Fortunately, he left all his ouvres and books there to his friends ! Terrible “ mistake “ to come back…

After that, there was the liquidation of the Institute and the personal freedom was restricted to a minimum with another arrest with suspicions of spying and engaging in counterrevolutionary activities while abroad. This caused even more acute poverty, near starvation.

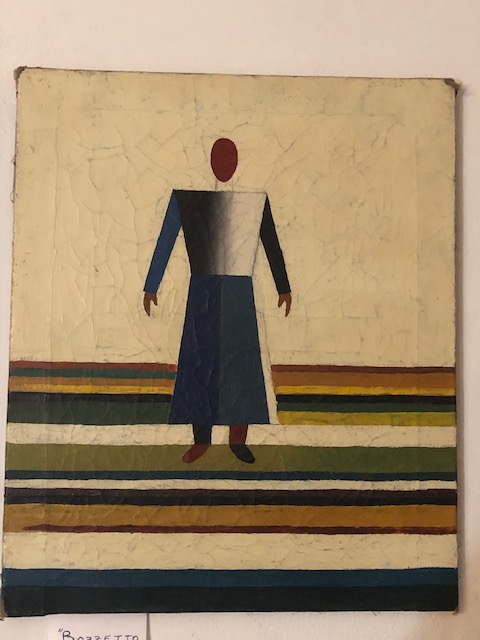

In this period, he went back to the figurative, but figures stand motionless in an elementary landscape, they are faceless, without beard, without arms, eyes, nose, ears. Malevich doesn’t see anymore the man of the future, or better, the future for men has become an unfathomable enigma. People become mutilated mannequins, prisoners in a criminal gulag; in this prost-suprematist period, its peasants become robots with a metallic appearance: a humanity in the throes of a nihilistic, apocalyptic destructiveness, stiff in anticipation of the end of the world.

There was acute cold in the apartment and the studio, with lack of proper shoes and warm clothes. From that the beginnings of cancer ( it is known he was tortured in jail ), being recommended by doctors to immediately go for a therapy abroad with a real possibility of a therapy in Paris or elsewhere to be paid for with proceeds from the sale of paintings left in deposit in Berlin. The passport application was rejected ( no material trace of the decision anywhere… ), with a de facto house arrest.

On the basis of correspondences and family members’ and friends’ testimonies, the party in power at the time, its organs, bear the moral responsibility for the premature death of Kazimir Malevich, an artist at least undesirable for the regime. The collapse of the totalitarian system saw the publication of many objectives , revealing works by researchers in Russia and abroad.

The ‘organs’ ( which is how the secret police was commonly called ), probably well aware of Malevich’s critical health condition, did nothing ; this suggests that the Lubyanka ( the KGB headquarters ) waited for the natural solution – death. And so it happened. Was it a deliberate strategy, a de facto criminal method to get rid of an aesthetical dissident ?

We know now of one of the KGB officials’ words: ‘Don’t touch the old man,’ meaning ‘do nothing, wait, let it happen by itself.’

We know the details of Malevich’s original design of his own coffin ( execution by Suetin ). An elongated, suprematist shape with offsets and profiles. Suprematist symbols on the lid, a square, a circle: His final expressive gesture, his message for the world, indomitable even then, suffering.

Malevich had also asked for his body to be given a vertical and horizontal form – arms spread. He himself, his body, was to play the role of a sign, “Supremus”. How to fulfil that wish? We must recognise the surrounding space step by step. The devil, as they say, is in the detail. The narrow entrance door, stairs, backyard staircase ( its appearance, inconveniences, described in several memoirs ) made any complicated manoeuvres with the catafalque impossible, threatening to violate the body’s integrity and everyone present was aware of that.

Following the liquidation of the Artistic Culture Institute, some Soviet institutions moved into its premises. The artist and his family were allowed to remain in the three-room flat no. 5, but the front door was walled up, cutting the residents off from the main staircase. The door connecting the apartment with what used to be the Institute’s premises remained in place, like a stage prop. Behind it was a wall. That left only the back door, the servants’ entrance, or “black entrance”, a deliberate step to humiliate the artist, then still artistically active, visited by friends, family members, guests and visitors.

The photograph showing the catafalque being taken outside, carried by Suetin and Rozhdestvensky, bears the legend ‘The catafalque being escorted from the Artists’ House’ – and not from the apartment and through the back door. They had to remove the body from the coffin to be able to negotiate the latter through the door. When they were escorting the coffin from the apartment, they had to put it upright because the stairs were very narrow.

A plaque with the ‘black square’ was affixed to the rectangular coffin. An appropriate plate on a nearby tree. Soon the symbolic structure with the suprematist ‘black square’ disappeared. The field overgrew with weeds and after the war it was ploughed. Some hand removed that piece of evidence too. It is possible that this time it was not the hand of the ‘organs,’ but that the artist’s mystic, cosmic vision fulfilled itself.